Artificial intelligence and satellite imagery are used in several projects for data collection, processing, prediction, and recommendations. Digitization makes life easier for farmers and automates certain tasks that are difficult or impossible for humans to perform.

Developed countries have the infrastructure and resources to make rapid progress in this area. In Africa, our resources and infrastructure are more limited. But we are making progress that benefits medium-sized and small farmers. As for large farmers, they have the means to use platforms in advanced countries and introduce more expensive and original innovations.

However, scientific research is open and international. Our collaboration with European and American researchers gives us access to the latest technological advances. Of course, some services are beyond our means. Thus, some satellite images are paid while others are free. We make the best use of the latter. There is certainly a difference in results, but it is not so enormous. So, if thanks to free images we manage to make yield predictions that are 80% reliable instead of 90% with paid images, that’s not so bad and much better than the results obtained by traditional means. Obviously, our progress does not allow states to finance research and its implementation and improve infrastructure, similar to the investments of the Green Morocco Plan.

Artificial intelligence is primarily a matter of data. We compensate for our lack of data in this area by using foreign public data, particularly European data. We test them on African countries. And we sometimes obtain conclusive results. This is the case with so-called optimization models, known as crop models. These are predefined, ready-to-use models. They are generally Australian but are used all over the world. We test them on African samples with satisfactory success rates. The models migrate.

As for our infrastructure deficiencies, they are not insurmountable. The existing internet structures are more than sufficient for the preparation, training, and application development phases. The next phase of using these models by farmers does not require internet connections. I can install an application on a simple smartphone; it will work without the internet. It is the improvement of the application that will require an internet connection.

The focus of Abdellatif Moussaid’s research

Abdellatif Moussaid’s research focuses primarily on the application of artificial intelligence and data science. His most recent work concerns precision agriculture:

- Precision agriculture and remote sensing: the focus of his research is the integration of advanced technologies to optimize agricultural production.

- Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning: Use of sophisticated models (such as hybrid CNN-LSTM models) to analyze large amounts of data.

- Remote sensing: he uses satellite data, particularly spectral indices, to obtain information on crop conditions.

- Crop Models: Development of models to predict and manage crop needs.

Other areas of Data Science: His areas of expertise also cover:

- Big Data and Business Intelligence: decision support

- Computer vision: image and video analysis, often in connection with remote sensing.

- High Performance Computing: necessary for quickly processing large volumes of data.

Models

We configure and calibrate “imported” models by integrating regional climate data. We do not use them as they are. Our recommendations are targeted. Sometimes, we only use a model’s algorithm. We retrain it, subjecting it to a second learning process in new climatic conditions and a new environment to ensure it is reliable and accurate.

We also develop our own algorithms specifically dedicated to specific tasks. Recently, we developed a fertilizer recommendation model with a focus on NPK. Its three ingredients are nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus. They are used in all crops. Our model takes into account climate data and free satellite data to recommend the quantity and dosage required for a given plot. It optimizes fertilization and helps avoid both under-consumption and over-consumption of fertilizers, both of which are harmful.

We have also developed yield prediction models that are 80% accurate two to three months before harvest. These predictions are of significant economic interest, particularly with regard to imports and exports of the crops concerned.

After focusing on tree crops and citrus fruits, I am now devoting my research to olive trees. We are doing precision work, tree by tree or in groups of trees. We are even trying to count the number of fruits per tree. Our recommendations concern fertilization and irrigation. We have developed an irrigation system that optimizes the use of water resources. This is an important issue for arid or semi-arid regions. Our predictions are financially vital for farmers who pre-sell their crops.

Robotics

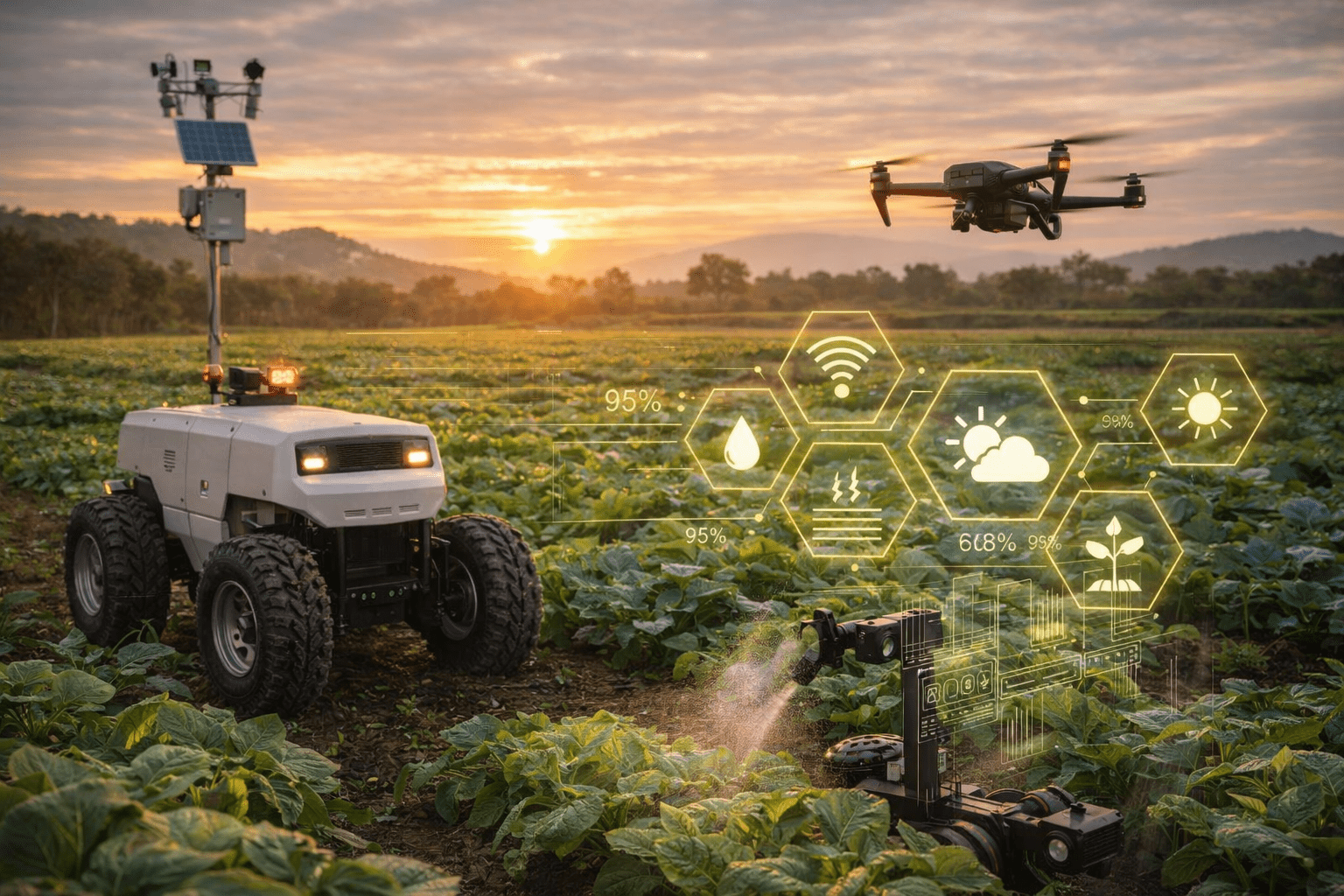

The Internet of Things and robotics are natural complements to AI. They allow us to create small robots capable of performing tasks that are difficult—sometimes impossible—for humans to accomplish. These robots are particularly useful in large orchards.

It is very difficult for a person to move from plot to plot, examine each tree, and assess its health. Robots and drones, on the other hand, can easily perform these tasks. They can detect the specific needs of each tree.

The drone, the Raspberry for example, carries a computer equipped with a model that prescribes the tasks to be performed. Thus, computer vision enables image processing and decision-making. I work on many images: RGP images (the most used color model for digital display), smartphone images, satellite images, and spectral images.

AI, IoT, and robotics are interdependent technologies whose common framework consists of data, data processing, and decision-making. We do not currently have a platform that brings all these elements together. However, we publish and exploit the results in the form of scientific papers, software, or applications. We are considering creating a platform that integrates all of our results. It will have the advantage of being directly usable by farmers.

However, we have experimental farms that allow us to test our applications and equipment on several categories of crops. The results are often conclusive.

Economics, ethics, and the environment

Our applications come at a cost. Farmers will only buy them if they believe in their effectiveness and can afford them. Their purchase is subsidized in several regions of Morocco. We have thus convinced many farmers to adopt quinoa cultivation, which is undemanding in terms of soil type, whereas cereals require specific environments. Generally speaking, small farmers are able to make decisions using a smartphone connected to a sensor.

The adoption of apps and robots risks widening the gap between small and large farmers. We must address this challenge. A related issue is that of ethics. In Africa, in particular, there are no laws governing artificial intelligence and its applications. Thus, the issue of data ownership has not yet been resolved. Transparency is the second challenge.

While our software and algorithms do not directly impact the environment, they are part of the broader framework of agroecology and greenhouse gas reduction.

Biography of Researcher Abdellatif Moussaid

Abdellatif Moussaid is a researcher in AI, crop models, and remote sensing in agriculture at Mohammed VI Polytechnic University. He holds a PhD from ENSIAS, Mohammed V University, in data science for citrus yield prediction and a master’s in Big Data Analytics from Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University. He was a research professor at Mundiapolis University, a digital administrator at the Ministry of the Interior, and a researcher in AI and agriculture at MAScIR Foundation.